The word “serendipity” comes from Sri Lanka. More precisely, it comes from an old Persian name for the country, Serendip. Coined by the British writer Horace Walpole, it was first used in reference to an old Persian fairytale about three princes from the land of Serendip. Through a combination of chance and intellect, they become the beneficiaries of a series of fortunate events.

A land as courteous as the morning sun, Sri Lanka exudes warmth. From the top of its peaks plumed with vanes of tea down to the toes of its beaches lacquered white by the froth of breaking waves, its nature and residents smile in harmony. But it wasn’t too long ago that this tear-shaped island cropping out of southern India was embroiled in a vicious and bloody civil war. The fighting—a spillover of postcolonial tensions between an ethnic Sinhalese majority and separatist Tamil forces in the north of the country—lasted more than a quarter of a century. Since the end of the war in 2009, serendipity is finding its way back to Sri Lanka. Today, those with the good fortune to discover this floating garden in the Indian Ocean will find themselves in a sea of pleasant encounters.

The most popular Sri Lanka circuit combines an adventurous week in the mountainous central highlands with slower-paced sightseeing along clement coastlines and seaside villages. Those with the luxury of time can venture north to remote Jaffna, where beguiling cloths of turquoise lagoons, emerald palms, and towering golden temples drape the land in color and mystique.

Tip: The following sections are divided into four rough geographic regions: the Backpacker’s Route covering central Sri Lanka, the Southern Province, Colombo to the west, and the Northern Province. Use the time references to customize your Sri Lanka itinerary for one, two, three, or four weeks.

The Backpacker’s Route

7-9 days: Kandy • Matale • Dambulla • Sigiriya • Nanu Oya • Nuwara Eliya • Ella

Colombo may be the de facto capital, but the spiritual center of Sri Lanka—one of the most devout countries in the world—is in Kandy. The most classic backpacking trail begins here, after a two-hour drive from Bandaranaike Airport into the hilly countryside, where the first glimpses of spice gardens and tea factories can be seen. A manmade lake, teal and angular like a large synthetic gemstone, is the centerpiece of Kandy. By its shores, the mood is serene and jovial. During the wet months of December and January, the city is awash in the smell of new-fallen rain. And in the mornings, the streets ring with the bell-like laughter of boys in pinstripe ties and girls with slicked braids. They pause briefly by one of the city’s many roadside shrines, time just enough for each pupil to leave a flower or a quick prayer before continuing on to class, now under the watchful protection of Buddha.

For more than 2,500 years, indigenous Sinhalese and Tamil monarchs ruled over different parts of Sri Lanka. Kandy was the seat of a monarchy which lasted from the 15th to the 19th century. By 1592, the Kandyan Kingdom was the last remaining independent power on the island, having resisted invasions from both the Portuguese and the Dutch. But eventually, it too relinquished its sovereignty. In 1815, all of Sri Lanka was absorbed into the British Crown under one name: Ceylon.

Throughout the colonial years, Kandy retained its cultural status and religious significance due to its royal palace and the adjacent Temple of the Sacred Tooth Relic. (In the context of Buddhism, relics are objects—commonly pieces of teeth or bone—retrieved from the cremated ashes of enlightened individuals. The Sacred Tooth Relic of Kandy is believed to have been Buddha’s left canine tooth.) Thrice per day, worshippers and visitors alike can catch a glimpse of the casket containing the sacred tooth, which for centuries conferred whoever possessed it a divine right to rule the land.

Dusk at the Temple of the Sacred Tooth Relic, or Sri Dalada Maligawa as it is locally known, is a particularly magical hour. Next to the glowing blue of Kandy Lake, the subtle colors of the temple grounds are illuminated by throngs of Buddhists clad in pristine white. Filing barefoot into the temple, they bring offerings of cut purple lotuses and water lilies and arrange them lovingly over the altars, so that the entire table eventually appears to be made of flora. Outside, as caretakers sweep the floor, they stir up the scent of jasmine.

The former capital also gave its name to the Kandyan dance, an important cultural export and unique symbol of Sri Lanka’s Sinhalese heritage. The most popular form of Kandyan dance, called Ves, began as a purification ritual and is performed only by men. The Ves dancer, adorned in a chainmail of silver petals and ivory beading made even brighter against his cinnamon skin, is a yin-yang of beauty. Every detail of his costume—from his pleated skirt to his mango-shaped earpieces and the tail-like tassel of his headpiece—attracts attention. Wherever he walks, eyes cannot help but follow. Today, Ves dancers can be seen all around Sri Lanka and are a fixture at festivals, where they are often accompanied by turbaned Kandyan drummers and decorated tuskers.

Next to Kandy Lake is the city’s Hela Bojun Hala. A no-frills food court run by the Ministry of Agriculture, it is a popular place for locals to gather and have a meal. Owing to its use of only fresh and local ingredients, there is no better place than a Hela Bojun Hala for a first encounter with Sri Lankan cuisine. Typical fare such as string hoppers filled with coconut sugar, donut-shaped wade, and tangy soursop juice can be enjoyed for mere cents. Steps away, the main streets of Kandy are lined with more eateries where one can dive deeper into Lankan flavors like fish roti filled with umami shrimp paste and elawalu roti—piquant vegetarian triangles made from potato and curry leaf.

Near the clock tower of Kandy, the bus station is a pandemonium, a wild scene flooded by the voices of fare collectors broadcasting their routes. It’s an overwhelming sight, but there’s no need to ask around for directions. The information finds you. “Where are you going? Dambulla Cave Temple? Get on.”

The express bus from Kandy to Dambulla is a wonderful little thing. A seat in the air-conditioned van costs a little over 500 Sri Lankan rupees (US $1.50). Rolling north in a straight line, it passes banana leaves as tall as two-story buildings, Moorish villages beset by jade mosques, and the mountainlike kovil of the Sri Muthumariamman Thevasthanam—a Hindu temple constructed in the Southern Indian or Dravidian architectural style.

The Rangiri Dambulla Cave Temple is located before the terminus in Dambulla. Across its series of five caves are painted ceilings, murals, and more than 150 statues of Buddha and other bodhisattvas—Buddhist deities dedicated to helping the earthbound attain enlightenment. Some are hewn right out of the rock. As early as the first century BC, these caves have been the site of a monastery. There is evidence that prehistoric Sri Lankans dwelled here prior to the arrival of Buddhism on the island. Inscribed as a World Heritage Site in 1991, Dambulla’s cave temple complex is the best-preserved and most grandiose in all of Sri Lanka.

A 30-minute tuk ride away is the village of Sigiriya, coddled by tranquil water gardens and a string of bohemian restaurants and cafés. Nature reigns freely here. Everything is flourishingly verdant, with the exception of a thin thread of burnt orange road. Perhaps it explains why one of Sri Lanka’s earliest names was Tambapanni—“copper-colored.”

From the canopy of the tropical forests rises a pair of breast-like mounts. One is Pidurangala, atop of which the best view of Sri Lanka’s Central Province unfurls. The other is Sigiriya. On its summit are the ruins of an ancient fortress. During the fifth century, a Sri Lankan king by the name of Kashyapa selected this protruding granite column as the site for his new capital. The gates to the city, found halfway up the rock, were carved in the form of an enormous lion. Only its paws survive to the present day.

Lions continue to hold a special place in the identity of Sri Lankans. Aside from being featured on the national flag since the days of the Kandyan Kingdom, the animal has lent itself to the name of the Sinhalese people, their language, and even Ceylon, which traces its roots to the Sanskrit word simhala, meaning “lionlike.”

The Central Province is one of nine provinces which make up Sri Lanka, and it is well known for its production of the famous Ceylon tea. It’s been over 50 years since Ceylon gained independence and became Sri Lanka, but the colonial name persists and continues to be used proudly as a protected trademark and seal of quality—at least when it comes to tea. In vast terraces damp with dew, countless leaves are hand-plucked and carried to manufacturing plants for sorting, steaming, and drying. The tea estates here bear a distinctive Scottish flavor, christened with names like Edinburgh, Glassaugh, and Hatton. They were given by the merchants who pioneered tea planting in the region. In fact, not far off, in the neighboring province of Uva, the first factory of Scotsman Thomas Lipton still functions today as the Dambatenne Tea Factory.

Only around three percent of all Ceylon tea remains in the country. The majority of the wide array of black, green, orange pekoe, and white teas produced here are sent abroad. In recent years, Sri Lanka has been vying for the title of the world’s second-largest exporter of tea in a head-to-head race against its main competitor, Kenya—another former British colony.

A peculiar detail characterizes the highlands of the Central Province. In place of the unmistakable curlicues of Sinhala, many of the signs are written only in Tamil. The vast majority of tea plantation workers are ethnic Tamils of Indian origin. Unlike Sri Lankan Tamils in the Northern Province who have resided on the island for more than 2,000 years, Indian Tamils—also called Hill Country Tamils—are descendants of indentured servants brought from Southern India to Ceylon in the 19th century to work on the plantations. Distinctive from the ethnic Sinhalese in their language, dress, and religion, many can be identified by a pottu—a visible ritual marking in the form of a red dot placed in the middle of the forehead. Every day at dusk and dawn, Tamilian tea pickers can be seen filing along on the railway tracks of small villages like Nanu Oya. The ballast and sleepers of the railroad are not only there for wheels, but also for human feet, on the way to and from a long day’s work.

Shepherding the tea terraces and estates are a handful of high-altitude colonial towns. Known as “hill stations,” in the past they served as retreats where colonialists could hunt, ride, and golf. Today, the hill stations lure a wider audience with their bygone charm and the promise of cooler weather. Best known among them is Nuwara Eliya, nicknamed Little England due to its meticulously preserved country cottages and old English-style lawns.

One of the best ways to take in the beauty of the Hill Country is by train. A ride on the Kandy—Badulla line, which passes through the backpacking sanctuary of Ella, is as photogenic as it is anarchic. With open doors that let riders hang daringly from the steps of the rolling train, its second- and third-class carriages have become a notorious tourist attraction. Forget about reservations here. No matter what kind of ticket is purchased, it is impossible to go against the flood of passengers all vying to board in Kandy. The zen tactic is to simply let oneself be carried by the current into any open carriage and space.

There is a palpable air of excitement onboard the Kandy—Badulla train. Perhaps it’s due to the adrenaline of getting on, or the carriages’ role as a washing machine of sorts, tossing commuters, tourists, Indians, Sinhalese, Moors, all together in one oversized load. There is no option but to smile and make small talk. By the time the train chugs into Ella, any agitation will have long been soothed by the misty landscapes and overpowering nature of human curiosity.

With its concentrated strip of restaurants, lounge bars, boho boutiques and blaring music, polarizing Ella evokes either a feeling of fondness or abhorrence. Of all the places in central Sri Lanka, it is the most touristically developed, and not always in the direction of convenience. Apart from the inflated prices of everything from king coconuts to tuk-tuks, indications to the popular viewpoint of Ella Rock have notably been obfuscated, so that those looking to navigate to the summit on their own are often forced to rely and tip the wily local “guides” culpable of covering them up. In spite of this, there are many redeeming qualities—and personalities—to Ella. Places such as the Nine Arch Bridge, a gargantuan feat of engineering from the British colonial era, remains a marvel in spite of the crowd. When the sightseers have waved off the last passing train, the night stirs alive to the rhythmic metallic chopping of kottu—flatbread cleaved into pieces and sautéed with meat or jackfruit.

At the Tunnel Gap Homestay, a cooking class with the hostess Sudha is a feast for the stomach and the eyes. The induction into the world of Sri Lankan home cooking includes dishes such as daal curry, mango curry, and brinjal moju—eggplant pickle. Guests can also try their hand at tempering, a South Asian cooking technique which uses spices such as curry leaves and pandan to unlock the flavors of a dish.

Tucked in the hills and reachable only by tuk-tuk or scooter is a thrillingly beautiful paradise. Above a borderless jungle tapestry is a natural rock pool dangling in the sky. Fed and polished by an incessant stream, it hides a precarious plunge. The carving water that disappears over the edge would go on to form Sri Lanka’s second-highest waterfall, Diyaluma Falls. With a name that means “liquid light,” it seems only right to crown Diyaluma as the highlight of central Sri Lanka. A short drive away is the rock temple of Buduruwagala, an ancient manmade wonder dating back to the 10th century. Behind a field of wild peacocks fanning their thousand eyes are seven colossal figures carved onto a single rockface: a large central Buddha, flanked by statues of various bodhisattvas. For those who seek it, the hills and mountains of Sri Lanka are steeped in spirituality.

The Southern Province

7-9 days: Dikwella • Hiriketiya • Matara • Mirissa • Ahangama • Unawatuna • Galle

Those who visit Sri Lanka without ever stepping into the country’s interior can be forgiven; the five-hour ride from Ella down to the nearest coastal city, Matara, can be a grueling journey. Around each full moon, known as a Poya, Lankan buses are rammed with straphangers hustling home for the monthly Buddhist holiday. The inside of the vehicles can feel like a tin can, with passengers pressed skin-to-skin like sardines. Or maybe a discotheque on wheels, as in the case of the unmistakable long-distance night buses. Adorned garishly with a riot of multicolored lights and decals, they blast an endless loop of Sinhala and Tamil music. Even when the buses are packed to capacity, vendors venture onboard to hawk their incense, their lotto tickets, their betel leaves. They burrow up and down the aisles, waving their goods in the air until the engines roar to life. The buses, regaining consciousness, lurch back and forth, signaling their imminent departure. Only then do the vendors scurry off. For 800 Sri Lankan rupees (US $2.50) from Ella to Matara, it is an unbeatably cheap way of seeing the country and a truly authentic Sri Lanka.

The Southern Province is an alluring playground, shaped by white beaches serving the best that life has to offer. Along Hiriketiya Beach, the waves dance and break into a surfer’s delight. In the adjacent town of Dikwella, the laid-back Garlic Cafe is an inviting setting to crack into a peppery crab curry. To the west is Mirissa, one of the most favorable locations on the planet for spotting the majestic blue whale. But the most indulgent surprise is perhaps in the seaside resort of Unawatuna, where a ten-dollar Ayurvedic massage under Anush’s firm hands kneads both body and mind to a higher plane. In these towns, every homestay and hotel has a culinary specialty up its sleeve. Mealtimes become seated excursions that delight the taste buds with faraway flavors. Even a simple breakfast can pull a surprise with dishes such as creamy kiribath milk rice and zesty pol sambol. The latter, an accompaniment made from freshly grated coconut and lime juice, embodies the essence of Sri Lankan cooking: delicate, fragrant, and tropical.

In between the towns are hideaways like Koggala Lagoon, known for its cultivation of cinnamon, and Ahangama Beach, whose transparent waters are lined with stilts. On mornings and evenings, sarong-wrapped fishermen can be seen sitting on top of them, patiently waiting for a catch—or for some cash from a photo op. Stilt fishing, which can be observed in this region of Sri Lanka’s southern coast, is a fairly young practice. Despite its traditional appearance, it only emerged after World War II, when food scarcity and overcrowding forced some fishermen to spread out directly over the water to find food. A fine place to watch them is from Mr. Sunil’s Roti Shop & Juice Bar, a humble beachside eatery overlooking the ocean.

Galle is the largest city and main cultural highlight in the Southern Province. Its charisma rests on the bastions of a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Dutch Fort. Within its fortified walls is an urban landscape that blends Asian and European architectural influences. Buddhist stupas stand side by side with colonial-era residences erected by the Portuguese, and later, the Dutch.

In the sweltering heat, Galle is a vision of romanticism. All around, young amorous pairs nuzzle like doves, seeking solace under the shadows. On particularly hot days with no more shade to shelter under, a myriad of restaurants and cafés offer a refreshing escape in the form of a pink falooda, homemade ginger beer, or a dotingly sweet wood apple juice. Just beyond the Dutch Fort, the city’s fish market bustles and brims with the freshest catch, trawled from the depths of the Indian Ocean.

Colombo

3-4 days

Sri Lanka’s largest city, Colombo, is often overlooked, even purposefully neglected, eschewed in favor of the country’s rural side. But what it lacks in natural beauty, Colombo makes up for with a metropolitan vibe and diverse architectural heritage. The city is home to an almost equal number of ethnic Sinhalese, Tamils, and Moors. It is also multi-religious, with large populations of Buddhists, Muslims, Hindus, and Roman Catholics. Each of these communities have contributed to the fabric of the city.

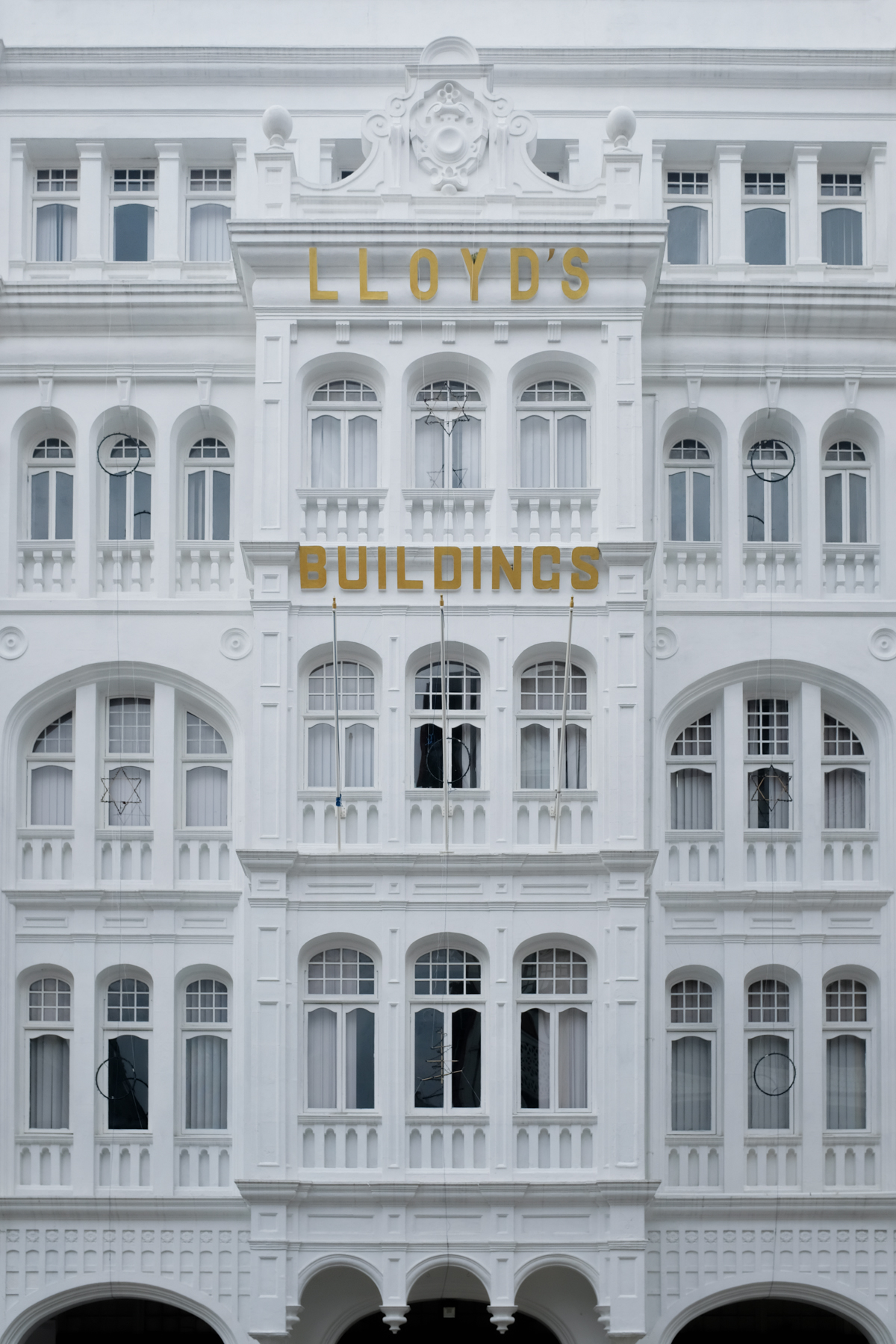

Its central business district, known as Colombo Fort, is a product of three European nations’ influences. The area was the site of the first Portuguese landing in the 16th century and used as a trading post. Later seized by the Dutch and eventually the British, Colombo became the capital of the whole island of Ceylon in 1815 after the fall of the Kandyan Kingdom. Today, the ramparts of the fort no longer exist, but many iconic colonial-period constructions still stand. Among them are the Clock Tower on Chatham Street that predates London’s Big Ben and the furnace-red bricks and Mezquita-like arches of the Cargills Building. Just outside the Fort area in a bustling quarter of the city known as Pettah is another fiery edifice. The Red Mosque—Jami Ul-Alfar Masjid—has been one of Colombo’s most recognizable landmarks since 1908. Commissioned by the city’s Indian Muslims, its mesmerizing pomegranate-shaped domes and swirling red-white patterns follow the Indo-Saracenic style of architecture, incorporating Indo-Islamic, gothic, and neoclassical decorative elements.

Traverse Pettah’s overwhelming crowds and bazaar-like streets towards Beira Lake to find the Pettah Floating Market. Once a putrid canal lined with abandoned warehouses, it has since been transformed into a quiet oasis for shopping where one can find an assortment of local handicrafts and clothing, including the tube sarongs worn ubiquitously by Lankan men across the country.

Situated on the Beira Lake is the halcyon Seema Malaka, a Buddhist temple constructed by one of the most influential Asian architects of the 20th century, Geoffrey Bawa. The son of an ethnic Sri Lankan Burgher (descendants of intermarriages between Portuguese, Dutch, and other Europeans with local Ceylonese), Bawa is celebrated as the “father of tropical modernism.” Austere in its appearance, Seema Malaka was designed for meditation and inspired by the forest monasteries of ancient Sri Lanka. The structure’s blue-tiled roof notably reflects the traditional architecture of the Kandyan era. A few minutes’ walk away is the Gangaramaya Temple. Regarded as Colombo’s most prominent Buddhist temple, within its grounds are a replica of Borobudur, the world’s largest Buddhist temple, found on the Indonesian isle of Java; a bodhi tree, the sacred fig tree under which Buddha sat when he attained Enlightenment; as well as an unrivaled collection of bodhisattva statues from around the world.

Tamils have also carved out their corner of Colombo. At the end of what is perhaps the city’s most photogenic alley, Sri Murugan Street, lies the Arulmigu Sivasubramania Swami Kovil. The temple is dedicated to Murugan, a Hindu god of war. Behind the gopuram, or temple gateway, Colombo’s Lotus Tower looms like a silent sentinel, serene and observant. At night, this colossal green pillar and magenta bulb blooms into light, illuminating the entire skyline in a fluorescent haze.

The best place to admire Colombo’s big-city allure is on Galle Face Green, a long esplanade that joins the city’s skyscrapers with the frothy sea. Each day, once the sun has reigned in its strongest rays, families, couples, and tourists alike gather under the open firmament: strolling, frolicking, and delighting in the abundant street food sold all along the length of the oceanside park. There are mango slices spiced with chili flakes, salt, and vinegar; cooked crabs; and isso wade, a quintessential snack made of deep-fried prawns and lentils garnished with chopped salad, lime juice, and curry sauce. However it’s cut, a slice of life on Colombo’s Galle Face Green is always deliciously savory.

The Northern Province

4-5 days: Jaffna • Nainativu • Keerimalai

The north of Sri Lanka feels like a world away from the rest of the country. And in many respects, it is. For one, Sinhala, the Indo-Aryan language spoken by most Sri Lankans, is not heard here. In its place is Tamil, a Dravidian language also used in the south of India and Singapore. As the two tongues are completely unrelated to each other, it is an oddity to witness even Sinhalese visitors switching to English while visiting the remote north of their country. For decades, this part of Sri Lanka was inaccessible, cut off from the rest of the island. Most of the fighting during the civil war took place here, with heavy consequences for the region’s infrastructure and development. Only within the last 15 years has the Northern Province finally begun to emerge from its long period of isolation. For these reasons, northern Sri Lanka has come to represent the country’s final frontier.

The first train to Jaffna, capital city of the Northern Province, leaves at 5:30 in the morning. While most of Colombo is still in bed, the mood inside Colombo Fort station is tense, laden with the pressure of claiming a seat for the seven-and-a-half-hour trip. As day breaks, like a summon to prayer, the droning voices of wade, corn, and peanut vendors ring through the carriages. Whenever there is more than one of them, their calls combine into a harmonious chorus, beautifully in sync with one another for a brief moment before breaking off and becoming disparate advertisements for their own goods again. On occasion, the train would jolt suddenly, gifting riders next to the windows a souvenir in the form of a slight bruise. The journey is long and strenuous, but a pretty one with glimpses into history, passing by impeccably suited stationmasters and vivid rice paddies that shine like glowing peridots. Apart from tinges of Tambapanni copper, Sri Lanka is green the whole way through.

The bats emerge long before the light starts to wane. Larger than gulls, they glide through the sky with wingspans as dark and wide as the coming night. Every evening at six, the sound of the nadaswaram reed, as grave and flat as a hooded cobra, pierces the air around Nallur Kandaswamy Kovil, drawing devotees through its golden nine-tiered gopuram for worship, or puja. Before entering, shoes must be removed, and men must also take off their shirts.

The steps of the kovil are often the setting of a cacophony, littered with mounds of brown coconuts. (The violent smashing of a coconut in Hinduism is a ritual of humility: only once the shell of the ego is broken does the path to purification and inner peace reveal itself. The water which flows out also represents the release of negative energy.) Elsewhere around the temple, devotees can be seen making offerings of milk or stroking a flame before bringing their hands to their eyes—a gesture for personal illumination. Inside, the atmosphere is euphoric. Light dances in every corner, set to the beating of barrel thavil drums and cumulus-like archways. Amidst a forest of golden pillars encrusted with hundreds of emerald-cut mirrors and metal trees that flicker with the auspicious glow of terracotta teacup lamps, even non-believers can find spiritual transcendence in the kovil of Nallur.

In the past, Jaffna was the second-largest city in Sri Lanka and an economic hub. More than 800,000 Sri Lankan Tamils fled their homes as a result of the war, and nowadays, life is much slower up north. There are sections of Jaffna that feel unfinished, taken back by nature’s lush hands. On the main street connecting the railway station with downtown, chipmunks scurry between the rolling spokes of rust-bitten bicycles. Pedestrians in sandals and saris amble along; no one is in a particular rush. Some have foreheads and limbs smudged with ash. These Hindu markings, called tilaks, are worn as a decorative symbol, often to denote a sectarian affiliation. Further out, in Jaffna’s lagoon, mangroves with slender legs and leafy headdresses stretch and bathe in the shallow saltwater next to houses on skinny stilts. These delicate sea dwellings mimic the fragility of the region’s dependence on fishing. For many in the coastal area of the Northern Province, fish is the only source of income.

Off the coast of the Jaffna Peninsula is a small but notable isle called Nainativu. Once inhabited by an ancient tribe of serpent-worshippers, the Naga, it is now a popular pilgrimage site for Buddhists and Hindus alike. It is believed that Buddha himself set foot here five years after having attained Enlightenment.

On the northern edge of the island is the Hindu Nagapooshani Amman Temple. It is one of 51 sacred Shakti Peetas, shrines built over locations where the parts and ornaments of the goddess Sati fell when her body was dismembered. (It is believed that Sati’s anklet landed on Nainativu, while the rest of her body and jewelry were scattered across India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Bhutan.) Reaching Nainativu from Jaffna requires a small expedition, first by bus over a shaky road to the jetty of Kurikadduvan, followed by a stuffy fifteen-minute ferry ride. With passengers fitted like Tetris pieces in the hull of the boat, religious affiliations reveal themselves quickly. Buddhists visiting the shrine of Nagadeepa Purana Vihara can be identified by their white garb, while Hindus heading to the Nagapooshani Amman Temple can be spotted by their red pottu or tilak marking.

From Jaffna’s bus station, it takes 150 Sri Lankan rupees (US $0.50) and less than an hour to cross the Jaffna Peninsula. The ride is breezy and orderly, traversing fields of swaying palmyra palms and whiffs of mango and gasoline before reaching the quaint seaside village of Keerimalai. Here on the northern rim of Sri Lanka lies the Keerimalai Naguleswaram Kovil, one of the oldest shrines in the region. Just adjacent is an ancient natural mineral spring. Already reputed for its healing properties since at least the seventh century, the Keerimalai Spring is separated from the ocean by a mere stone wall. The water in the encased open-air pool is slightly brackish, a mélange of salt and warm freshwater that pumps into the well from a secret source. After a morning puja in the kovil, many come to enjoy a cooling dip. Under a tropic sun, the aquamarine spring glistens seductively with effervescent constellations of light. As remote as it is, Keerimalai comes perhaps the closest to encapsulating the magic and serendipity of Sri Lanka.

First published February 2024

Leave a comment